Susan Noh (‘96 DVM, ‘07 PhD) saw first-hand while growing up on a sheep ranch in southern Idaho just how difficult it can be to make a living raising livestock.

“You can’t control the weather cycles, you can’t control wildfires, and markets are international, so what’s happening in China and Russia and around the world affects the price of your meat and the wool,” said Noh, an adjunct faculty member in the Paul G. Allen School for Global Health and the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology at Washington State University

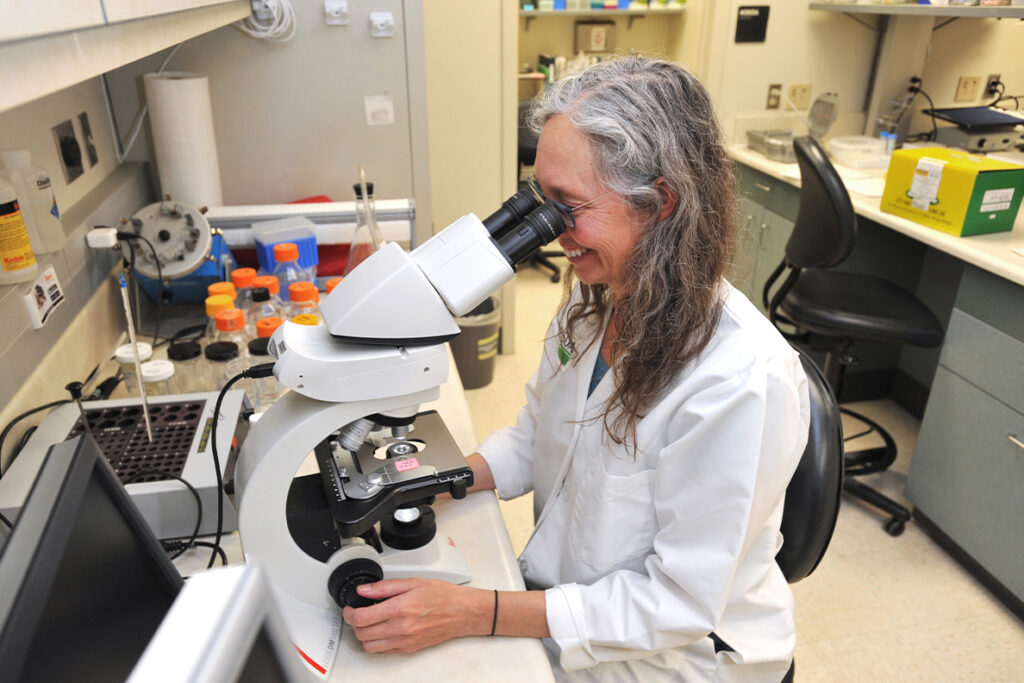

Noh, who is also a research molecular biologist with the United States Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service, strives to optimize animal health for farmers and ranchers by collaborating with researchers from the USDA and across the WSU system.

Her research mostly deals with tick-borne disease, in particular bovine anaplasmosis, an infectious blood disease in cattle. The pathogen, Anaplasma marginale, is transmitted through the tick’s salivary glands and into the host when the tick feeds.

The bacteria make its way into the bloodstream and infects red blood cells, in some cases causing anemia, fever, weight loss, lethargy, abortion and death. In the United States, the Southeast and Midwest see the highest number of cases, although the disease is endemic in eastern Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

“In the U.S. there can be anywhere from 30% to 80% of cows in a herd infected. Some of those animals, don’t show any signs of disease, and other times you get outbreaks when you have unexpected death of a number of animals in a herd; it’s very unpredictable,” Noh said.

Much of the research would not be possible without access to live tick colonies housed and maintained at the USDA facility on the University of Idaho campus. Each colony contains thousands of Rocky Mountain wood ticks, which are known for spreading the disease.

“We can actually look at the pathogen in the cow and in the tick and complete the whole life cycle in an experimental setting,” Noh said.

It’s all surprising to Noh, who could have never imagined when she walked with her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine in the spring of 1996 from WSU that she would be working with ticks.

Currently, she is looking to understand what receptors on the pathogen and in the tick allow the Anaplasma marginale inside the host cell.

“We are trying to understand what the targets of an effective immune response would be, and if we can make an immune response that would then block the ability of that bacteria to get into the cell,” Noh said.

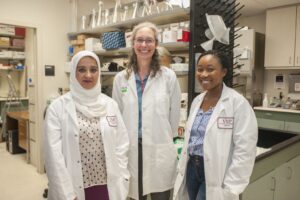

Noh said major advancements in bovine anaplasmosis research have been made by some of the doctoral students she’s mentored, like Forgivemore Magunda who examined how the pathogen replicates inside the host cell without being broken down and Muna Solyman, who demonstrated the requirement of iron for the pathogen..

“This work was really establishing the foundation of the niche in the tick that allows anaplasma to replicate, and that’s work I’m particularly proud of because it had never been done before with a tick-borne pathogen,” she said.

With the aid of the scientific community and the drive of her students, Noh is confident a way to block bovine anaplasmosis can be discovered in her lifetime.

“Through time I’m more optimistic about it,” she said. “The things we are starting to work on now and the things we’ve done the past five years, I think it is possible.”