By Linda Weiford, WSU News

PULLMAN, WASH. – This month’s Thanksgiving turkey might contain more than bread stuffing. It could also harbor salmonella, a bacterial pathogen that causes foodborne illness in 1.2 million Americans each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

PULLMAN, WASH. – This month’s Thanksgiving turkey might contain more than bread stuffing. It could also harbor salmonella, a bacterial pathogen that causes foodborne illness in 1.2 million Americans each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That’s why molecular epidemiologist Margaret Davis of Washington State University’s Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health prepares turkey “as if it’s contaminated with salmonella. When handling any type of poultry, I err on the side of safety,” she said.

As co-author of seven salmonella studies in the past 15 years, Davis should know. She investigates the many ways these pathogens are transmitted and why some strains have become resistant to antibiotics.

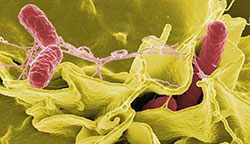

“Salmonella is an extremely robust organism,” she said; it has the ability to survive in a wide range of environments – from water and soil to, literally, the kitchen sink.

No. 1 cause of food poisoning

While most salmonella infections inflict mild to moderate gastrointestinal distress lasting 4-7 days, others leave a dark and permanent legacy, killing an estimated 100,000 people worldwide annually. Children, the elderly and people with impaired immune systems are most vulnerable, said Davis.

“Not only are salmonella bacteria ubiquitous in the environment, but they’re hardy,” she said. They make their way into many types of foods: Poultry, meat and eggs are the biggest targets, but disease outbreaks have also been tied to spinach and even peanut butter.

The organisms can withstand freezing temperatures, dry conditions, zero oxygen and high acidity inside the human gut. They can survive in soil and water for months and on countertops and cutting boards for weeks, she explained.

The secret to destroying the pathogens is to thoroughly clean and thoroughly cook.

“High heat kills the bacteria, so the biggest risk at home comes from undercooking,” said Davis. “People should also be aware of cross-contamination, which occurs when countertops, sinks and utensils aren’t adequately cleaned after the raw poultry or meat is handled.”

Say, for example, after trussing a raw turkey on a cutting board, you don’t thoroughly clean its surface before chopping lettuce. Lurking salmonella organisms could then contaminate both the knife and the lettuce.

Invisible residents

In many cases, salmonella’s journey originates in animals’ gastrointestinal tracts, a natural home for the bacteria.

“Many animal species harbor the bacteria without being sickened themselves, so there’s no way to tell by looking at them whether they are infected hosts,” said Davis.

Animals typically pick up the bacteria from contaminated feces in the soil. Also, food-animal carcasses can become contaminated at processing plants when exposed to tainted equipment, storage bins or even a person’s hands.

Large disease outbreaks have been traced to fruits and vegetables as well as poultry, meat and eggs. How do salmonella find their way to a field of tomatoes or cucumbers?

“Contaminated water used to irrigate fields can, in turn, contaminate the foods being grown there,” Davis explained.

Something goes wrong

Salmonella infections – whether caused by contaminated turkeys or cantaloupes – “represent something that went wrong somewhere along the pathway from farm to table,” said Christopher Braden, director of the CDC’s foodborne and environmental diseases division in Atlanta. “These bacteria cause more hospitalizations and deaths than any other pathogen found in food,” he said.

And that is why, at WSU’s Allen School, Davis continues her work to understand how salmonella bacteria get from point A to point B and beyond to ultimately carry out their dirty work.

Contacts:

Margaret Davis, molecular epidemiologist, WSU Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health, 509-335-5119, madavis@vetmed.wsu.edu

Linda Weiford, WSU News, 509-335-3581, linda.weiford@wsu.edu